The Audi Environmental Foundation and the Technical University of Berlin have announced that they are developing filters to deal with urban runoff. The filters will be used to prevent harmful substances, including tire wear particles, from entering bodies of water such as sewers and even rainwater. The collaborative project was first launched in September 2020 and will run for three and a half years.

It is estimated that 110,000 tons of microplastic end up on German streets each year, making its way into city sewers, soil, rivers and oceans without being treated.

Produced in collaboration with the department of urban water management at the Technical University of Berlin, filter manufacturers, software developers and water utility companies, the optimized URBANFILTER sediment filters will prevent the harmful effects of urban runoff. With a modular design, the filters can be easily adapted to provide solutions for an array of road layouts and other sources of pollution. They work by catching microplastics as close to their source as possible before urban runoff can occur.

“We also want to capture as many other pollutants as possible that accumulate on and around streets – beverage cans and cigarette butts, which unfortunately often end up on the sidewalk, as well as particles that are actually natural, such as sand, leaves and pollen from trees,” explained Joachim Wloka, Greenovation project manager, Audi Environmental Foundation, responsible for URBANFILTER.

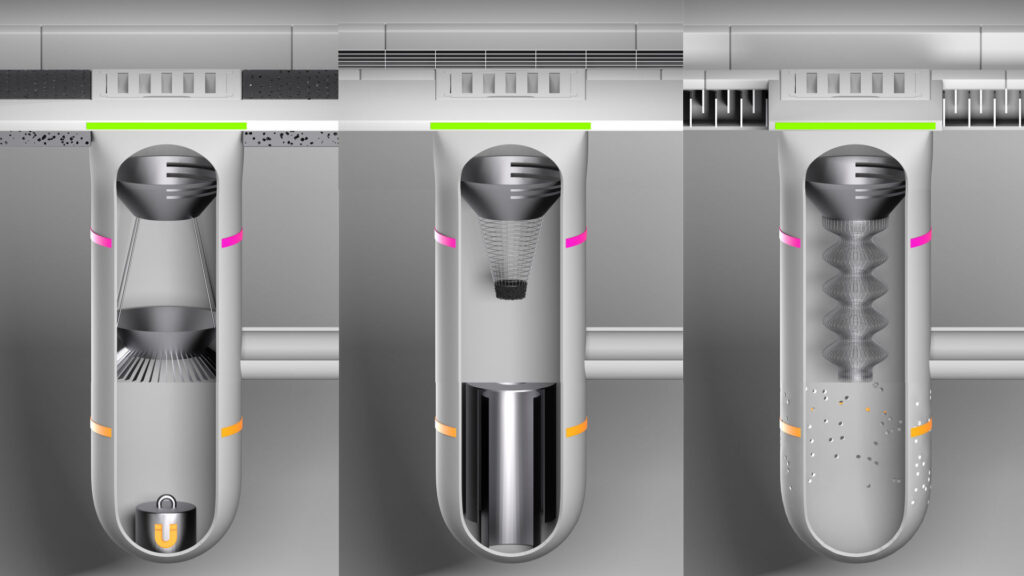

At present, the filters are divided into three zones: street, sewer and drain. In the uppermost street area, a special runoff channel or an appropriate asphalt will feature; under this, in the sewer section, larger solid materials are filtered out. Finally, in the lowest area (the drain), all the fine microplastics are filtered.

“In total, we are developing nine different modules for different road and traffic conditions,” explained Daniel Venghaus, a research associate in the department of urban water management at TU Berlin. “Up to three different modules can then be combined from this modular system to achieve the best result depending on the location.”

“We’re currently testing a magnet module here,” continued Venghaus. “In our preliminary tests, magnets trapped particularly fine particles without clogging.” With most of the modules still in the planning stage, the project partners aim to test them in real-world situations by the end of 2021.

The filters must be maintained and emptied at regular intervals, with street cleaning schedules, traffic volume, school breaks and weather all being considered for the intelligent connectivity of the filters.

“Based on all this information, we can predict each filter’s degree of contamination and determine when the best time to empty it is. It’s basically the same idea as predictive maintenance, which is commonplace in the automotive industry,” explained Wloka. “As a result, we’re connecting different sectors and applying optimized processes to a new application.”

The weather forecast will play an important role in the intelligent network of the filters because large amounts of rain cause filters to clog more quickly due to debris being washed into street drains.

“If the weather forecast predicts heavy rain after a prolonged dry spell, we’d be able to respond immediately and have street sweepers clean the road before the downpour,” commented Venghaus. “This would prevent the particles from entering bodies of water and the filter could remain in use for longer.”