Pirelli is pushing sustainability best practice right through its supply chain. Maureen Kline, North American VP of sustainability, explains

It’s one thing to focus on the sustainability of your own business by reducing its environmental footprint or by promoting ethical behavior among its employees. It’s quite another to ensure that those same high standards apply right down the supply chain of a product as complex as a high-performance tire.

Pirelli is trying to do both. In September, the company was named the world leader in sustainability in the Automobiles and Components sector of Dow Jones’s Sustainability World and Europe indices. It’s also working with competitors on cross-industry initiatives in the sustainability field. New sustainability policies – developed by a team in Milan and implemented around the world – seek to continuously improve the sustainability and traceability of natural rubber.

The move builds on an existing Green Sourcing policy that brings together sustainability expectations in Pirelli’s supplier selection process. In addition, Pirelli voluntarily subscribes to the independent Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) and expects its suppliers to do the same.

“I think that sustainability is moving forward at an accelerated pace throughout business because everyone is pushing it through their supply chains,” says Maureen Kline, Pirelli North America’s VP of public affairs and sustainability.

“We have expectations from the automotive companies that we supply, and we have expectations of our own suppliers. They acknowledge a sustainability clause that says they are conforming to our overall sustainability platform and they agree to be audited for their sustainability practices. We also reward them through a category in our annual supplier awards.”

Naturally better

In the area of natural rubber, Pirelli has a new policy to annually measure sustainability improvements in the supply chain.

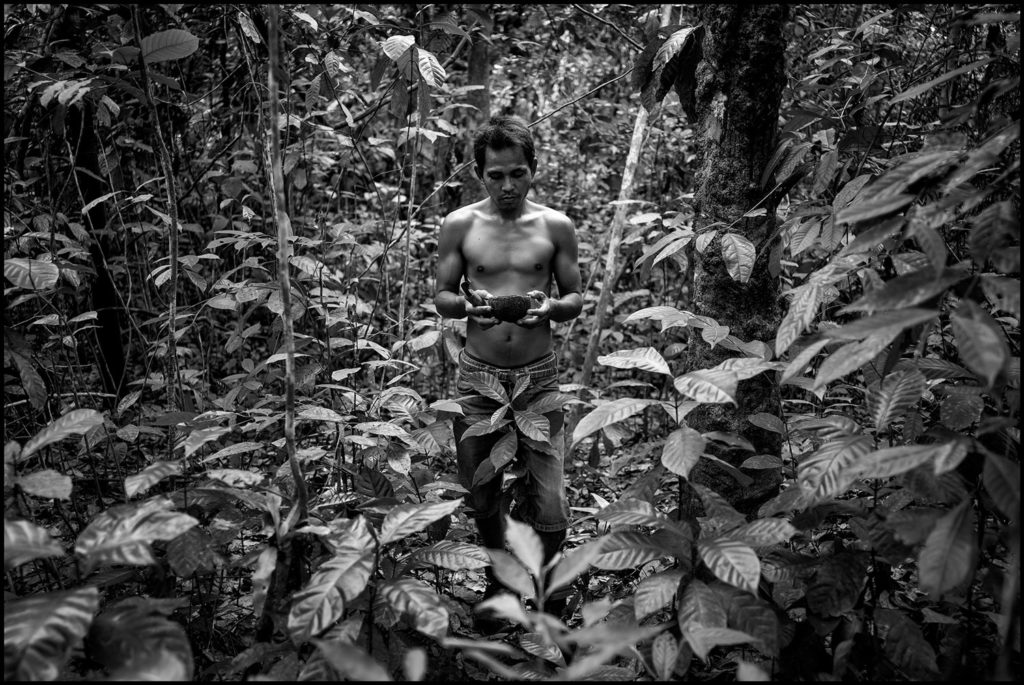

“Traceability in the supply chain is a journey,” assesses Kline. “In an ideal world, we would be able to trace all the components of every product down to their original sources. But natural rubber is one of the hardest materials to trace because there are, according to our calculations, approximately six million farmers worldwide in natural rubber cultivation. Approximately 85% are smallholders with 1-5ha and there are many layers of intermediaries before the rubber gets to us.

“The approach we took is to work in partnership with our Tier 1 suppliers. We support them in drafting a roadmap of activities aimed at cascading sustainability governance down the supply chain, improving traceability and implementing actions based on our 12-pillar policy. We report publicly every year on progress made.”

The 12 pillars encompass the whole system around natural rubber, everything from no tolerance for labor exploitation, to fostering the development of local communities and preventing deforestation. The policies were shaped by learnings and best practices in other agricultural streams such as palm oil.”

“We conducted a stakeholder engagement process to determine our approach, putting everyone from car companies to farmers around the table,” Kline (right) explains. “We did further consultation to come up with the implementation manual, which was published 12 months ago. We also published the Sustainable Natural Rubber Policy Implementation Roadmap 2019-2021 and a specific plan for 2019.”

“We conducted a stakeholder engagement process to determine our approach, putting everyone from car companies to farmers around the table,” Kline (right) explains. “We did further consultation to come up with the implementation manual, which was published 12 months ago. We also published the Sustainable Natural Rubber Policy Implementation Roadmap 2019-2021 and a specific plan for 2019.”

Aside from local collaborations through trade associations such as the US Tire Manufacturers Association (USTMA), where discussions around the circular economy can work toward creating new markets for end-of-life tires, Pirelli has also banded together with rivals on an international basis, helping to create the Global Platform for Sustainable Natural Rubber (GPSNR) to improve sustainability in the natural rubber supply chain.

Launched as a spin-off from the Tire Industry Project of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, the GPSNR, which includes representatives of tire manufacturers, rubber suppliers and processors, vehicle makers and NGOs, held its first general assembly in Singapore in March.

Beyond natural rubber

There are other, product-related sustainability initiatives, too, such as working toward full recyclability of the tire – a particular challenge for a company with a high-performance portfolio such as Pirelli’s.

“Product sustainability also means low rolling resistance,” Kline expands. “If you look at the CO2 emissions of a tire through a full lifecycle assessment – from raw materials, through production, logistics, use on the car and end-of-life – more than 90% of the environmental impact is when the tire is on the car. The single most beneficial thing that we can do in product sustainability is therefore to work on lower rolling resistance.”

Sustainable new raw materials such as silica from rice husk ash and innovations in new forms of mobility, not to mention the prospect of tires ultimately being sold as a service rather than as a product, with billing by the mile not the unit, are also on the sustainability department’s radar.

The payoff

The payoff

Within Pirelli, the sustainability department is combined with risk management. Mitigating climate and other risks at a corporate level is one important benefit of the sustainability work. Another is greater confidence from the investor community as it focuses on sustainability factors – historically more so in Europe, but now increasingly in the USA, too. Meanwhile the car companies are also taking note.

“Like us, they are including sustainability in their procurement processes, so that’s been an important competitive advantage for us,” adds Kline. “One of the definitions of sustainability is to create value for all your stakeholders, not just shareholders, so that’s what we try to do. There are reputational benefits to that.”

For all of its laudable initiatives, Pirelli’s reputation in sustainability – not to mention that of the tire industry as a whole – remains a work in progress, as Kline acknowledges.

“Many people don’t know a lot about tires and sustainability so there’s a lot of potential for education,” she concludes. “Some are under the misconception that tires are just thrown in riverbeds or go to landfill, when more than 80% of tires in the USA are repurposed into something else.

“I think it’s a bit of an untold story. It’s not well known, for example, that tire manufacturing has a lower GHG footprint in North America than other types of manufacturing because most of the factories are powered by natural gas. We have a long way to go, but we can get the word out that the tire industry is very high-tech, very focused on innovation and sustainability.”